LINE BREAK

[ezcol_1half]

The Tyger is a Tiger, Lyterally

To many scholars, William Blake’s poem The Tyger is seen as a metaphor. The popular argument concludes that the poem concerns the dissonance one feels in seeing the cruelty of reality in disharmony with the concept of a benevolent, monotheistic, and Christian God. These scholars suggest that the evil the tyger represents is crafted by the deity alluded to in the lines of the poem. I, however, argue that The Tyger references not the dissonance of the monotheistic agenda but rather the depravity of the classically polytheistic one through the monotheistic mindset. As such the tyger is not an allegorical reference to moral standing within the Christian sphere, but a subject outside of its ideology. In other words, the tyger is simply a tiger.

With The Tyger, Blake employs the poetic measures of enjambment[1], tag meter, slant rhymes, as well as outdated language, to create a sense of unease in the reader. This unease is intended to mirror his own feeling[2] on the matter of polytheism, thus solidifying his stance against it. While the tyger does not represent evil, per se, it does allude to the chaos of polytheism—and control being a staple desire of mankind, chaos is unfavorable. Unlike in monotheism, there is no being that is wholly good. There are not polar opposites such as good and evil, and so to try to measure the tyger on such a scale is a misled venture. Therefore, the poem is not intended to be encapsulated in the solitary sphere of Christianity, but rather human history as a whole.

While at first it seems Blake is asking what deity[3] could fashion such an intimidating presence as that of the tiger, on second glance the reader may note the “or eye.” This suggests that the question is one such as “who could even imagine (eye) such a thing?” Certainly when considering the limitless power of a deity, such as the Christian God, the creation of the tyger is unquestionably possible—in fact, it is likely an altogether trivial project. The omnipotent deity would be able to craft exactly what he wanted. To question this would be blasphemous. Thus, it is obvious that Blake is not referring to such a creator, but rather the more power-limited gods of yore. This is suiting for polytheism as the gods in such a faith are more akin to the people they reign over than to perfection.

It is noteworthy to articulate that the gods of polytheistic religions are analogous with the natural elements[4] of their follower’s environments. This coupled with the regular praying to the deities, granted the individuals of the time comfort in that through their wishes and pleading they felt the security of having some control. When there was a thunderstorm, it would be assumed the god Zeus was angry, and sacrifices could be made to appease him. Seafaring Greeks prayed to Poseidon for good winds and smooth seas going so far as to sacrifice herd animals such as lambs to pacify him. There was control through tribute. By Blake’s time these deities were seen as simply occurrences of nature. Comfort came from an all powerful God, who worked in strange ways. So when nature turned destructive, it was seen as a tool of God’s will, and not chaos. Chaos, without some personal control or sense of divine protection, solicits fear, and this is what the tyger in Blake’s piece serves to remind the reader of.

To draw a parallel, Blake is not only suggesting that the polytheistic gods are simple misperceptions of nature with his stance, he is suggesting very clearly that the tyger is equally grounded in the corporal realm of Earth. Take the “fire” of the tyger’s eye for instance. The fire is likely a reference to the tapeta lucida[5] layer of tissue in the optical organs reflecting light. The tyger’s “eyes” appear to have already existed in some “distant deeps or skies” (Strand 143). Distant, or in other words, out of the creator’s reach, in the past, before a creative hand came along to “seize the fire”, implying that the tiger was already in existence, and was simply plucked from it by the deity, or simply always in existence. The burning fires of the tyger’s eyes simply garnered attention. Blake also uses the line “In the forest of the night” (Strand 143), which suggests further that the tyger already existed, as forests are fully grown and as it is night it is passed the prime time of day. Thus the term “frame thy fearful symmetry” (Strand 142) represents a mere illustrating or rendering of the features of either a more ghastly beast or an equally terrifying one that was already in existence. Even looking at the mere mention of “forests” and subsequently “deeps or skies,” the reader is left with a sense of division, as is characteristic of polytheistic beliefs, such as the Greek Poseidon, Zeus and Pan, or even the tree nymphs, Dryades.

The tyger, existing in a physical form, is acted upon as an object in that it is “framed.” Like the rhyming couplets of its stanzas, The Tyger pairs a straightforward description of a tiger with a set of philosophical questions; however, it is the beast’s placement in time that explicitly insists that the tyger is a literal being and not a metaphor. So while it could still demonstrate or evoke a sense of maturity, yet discord in man, it is not the embodiment of said attributes. Blake’s utilization of certain historical aspects of language lend themselves to this theory of time placement. The several uses of the ampersand[6], while he still uses the typical “and,” as well as the spelling of tyger with a Y, though outdated even in Blake’s time[7], suggest that the poet tried to evoke a sense of historical, ancient foundation of the beast. Further compounding the sense of age is the line “What the hammer? What the chain?” (Strand 144), that, very crude in its grammar, and simplistic in its execution—like that of the musings of a caveman caricature—calls to mind a sense of the primal, and thus it almost seems to be the tyger’s thought channeling through the writing of the poet.

Just as Blake suggests the tyger’s creator, or transporter, reached into the past for inspiration, reaching further into the poet’s writings makes clearer his intent. The sister poem to The Tyger, The Lamb offers some clue into the poem’s meaning. [/ezcol_1half]LINE

BREAKIt is clear that the “Lamb” refers at one point to a messiah—a Lamb of God or a follower of the Christian God—yet the poem speaks largely of the animal as well, as is apparent in the line, “I a child & thou a lamb, we are called by his name” (Erdman 9). The two lines of the poem separate three subjects, the “I” being the poet and a childlike being, the “lamb,” with the lower case L representing the herd animal, and finally “his” with a lower case H, the messiah but not God. The sense of unity in the adoption of monotheism is illustrated in the peaceful nature of the poem. In contrast, the fearful symmetry of The Tyger glares by the other poem’s side, chaotically.

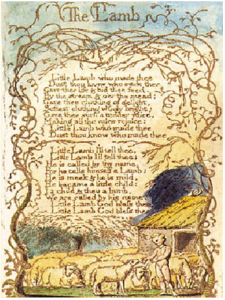

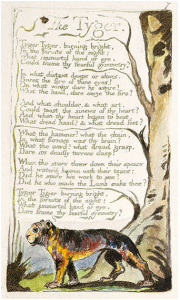

Looking at the two poems as units, it is clear The Lamb is more fluid and malleable in its structure, and The Tyger is rigid and uniform, thus hinting that polytheism is set in its ways. While the uniform structure of The Tyger illustrates the idea that polytheism is ultimately understood, the question marks throughout (figure 1) indicate that it is not accepted, and questioned. Moreover, the more simplistic of the poems, The Lamb, appears to be not so much a series of questions, but a nudge, urging youth to accept their origin from the Christian creator, God. Note that it does not contain even a single question mark, as Figure 2, Blake’s original print, indicates, unlike the The Tyger which is riddled with them. Furthermore, The Lamb consists of only two singular blocks of text, representative of a single God and his method of creation, and earth bound Jesus, frequently referred to as the lamb, whereas The Tyger is broken into several pieces, representative of the multiple gods of polytheism.

Unlike the “masculine true rhymes” that “slam the door shut” (Oliver 53) the slant rhymes of Blake’s The Tyger in “eye” and “symmetry” in the first, and especially the last, stanzas also imply a sense of unease. Whereas The Lamb refers to a peaceful existence, with a single, non-conflicting, God, The Tyger gives a sense of chaos with the inference of classical polytheistic gods. Again looking at the line, “In what distant deeps or skies” (Strand 143), we find an allusion to gods of the sea such as the Greek Poseidon, who was often in disagreement with the other gods such as Zeus, as well as an open inquiry into the origin of the nature of the beast as it is of no use to man as the languid, nourishing lamb is. This is especially important when paired with the lower case H in “he” when asked if, “he who made the Lamb make thee?” (Strand 143), in that the gods could only act on an object, not an idea, much less a metaphor. Moreover, with the reference to “deeps” the poet suggests that the tiger is out of place in the world of man, as if dragged up from a nasty community in the seabed.

Blake translates this sense of fear to unease in his poem. Just as in Mary Oliver’s example of “hickory | dickory | doc[8]” (50), there is a tag (the syllable in “doc”) at the end of Blake’s lines. His use of rhyming couplets, in addition to this off-putting, impure foot at the end of his lines, mirrors his inference to the chaos in the belief of polytheism and also the fear invoked by the tiger. And terrifying tigers were in that time that Blake wrote the poem—not caged zoo attractions or part of magic shows, but something of nightmares. In fact, even several decades after Blake’s time (c. 1757 – 1827) there was a great fear of tigers. For example the Champawat Tigress (1907) slaughtered an incredible number of people as its eventual killer, Jim Corbett, explains, “The tigress… had arrived in Kumaon as a full-fledged man-eater, from Nepal, from whence she… had killed two hundred human beings, and during the four years she had been operating in Kunaon had added two hundred and thirty-four to this number” (3). It is clear with the capacity of this single tiger to kill, that the animals posed a very real danger to man back then—far more so than today.

The fact that the entire poem is a series of questions demonstrates a sense of unknowing even in the mind of the author, as he is pondering the entirety of the piece and this plants a similar seed of wonder in the reader, which, given that mankind is afraid of the unknown, further augments the argument that The Tyger is a poem of unease.

Overall, The Tyger seems to suggest a general admiration by the said polytheistic gods of the fearsome tiger, which is actually, upon closer inspection, a condemnation. The rest of heaven, or the gods, “threw down their spears” (Strand 144) which at first is perceived in the sense of throwing down arms, as the “watered” in the following line gives the impression of something peaceful, as in watering a garden. In that case, the gods admire the beast and cry tears of joy. However, spears are a specific, poignant weapon, a projectile tool of death, thus the gods, afraid themselves to get near the tyger, are perhaps trying to drown or suffocate the savage flame of the tyger, which garners a greater sense of fear and subsequent respect by man than they do themselves.

A monotheistic god would have no fear as the tiger would be one of his countless creations, never surpassing his all powerful existence, however one of many less powerful gods would. Moreover, in the end Blake changes “could” to “dare” as in what god would “Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?” The enjambment after “eye” in the first and last stanzas emphasizes this shift from “could” to “dare” and illustrates in importance. Thus rather than suggesting a development from an innocent lamb to an evil, experienced tiger, Blake is offering the tiger as a throwback to a more primitive nature such as a polytheistic belief system. The peaceful lamb is therefore the more evolved, albeit dependent creature.

In conclusion, with its use of selective enjambment, slant rhymes, impure metric feet, selective capitalization, and intentionally outdated language, The Tyger portrays itself as a duality of deistic belief and sheer description of a bestial tiger rather than the metaphor of evil within the monotheistic sphere of thought that many believe it does. It seems to advocate monotheism, but only in direct comparison to The Lamb, as the discord polytheism provides is portrayed as unfavorable and fear inducing. In the end, perhaps to the dismay of the metaphor loving scholars and casual readers alike, the tyger is simply a tiger. However, it carries in its “deadly terrors (fangs)” a message that monotheism should be favored over classic polytheism if one wishes to live peacefully and avoid the chaotic “fire” of the beast’s world.

linebreak

linebreak

linebreak

Works Cited:

Corbett, Jim. Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1944. Print.

Erdman, David. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. New York: Anchor books, Inc, 1988. Print.

Oliver, Mary. A poetry Handbook: A prose guide to understanding writing poetry. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 1994. Print.

Strand, Mark and Eavan Boland. The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms. New York: Allentown Digital Services Division, 2000. Print.

The Tyger

By William BlakeTyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Could frame thy fearful symmetry?In what distant deeps or skies Burnt the fire of thine eyes? On what wings dare he aspire? What the hand dare seize the fireAnd what shoulder, & what art. Could twist the sinews of thy heart? And when thy heart began to beat, What dread hand & what dread feet?What the hammer? what the chain? In what furnace was thy brain? What the anvil? what dread grasp Dare its deadly terrors clasp?When the stars threw down their spears, And watered heaven with their tears, Did he smile his work to see? Did he who made the Lamb make thee?Tyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

1794

The LambBy William BlakeLittle Lamb who made theeDost thou know who made theeGave thee life & bid thee feed.By the stream & o'er the mead;Gave thee clothing of delight,Softest clothing wooly brightGave thee such a tender voice,Making all the vales rejoice!Little Lamb who made theeDost thou know who made theeLittle Lamb I'll tell thee,

Little Lamb I'll tell thee!He is called by thy name,For he calls himself a Lamb:He is meek & he is mild,He became a little child:I a child & thou a lamb,We are called by his name.Little Lamb God bless thee.Little Lamb God bless thee.

1789

[1] As defined by Oliver, Mary. A poetry Handbook: A prose guide to understanding writing poetry.

[2] Christian-Polytheism.

[3] Deity: in reference to the stated “immortal” as in “What immortal hand or eye…”

[4] Wind, fire, hurricanes, etc.

[5] Latin for “bright tapestry”—the reflective tissue just behind the retina, that is found in many vertebrae.

[6] Ampersand symbol: &

[7] 28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827